Connectedness & Belonging

We all have a drive to survive and a longing to connect. It is only when we feel safe are we then able to fully connect with ourselves and others.

Workplaces can be a place of reactive survival, especially now as people are coming back into the office. This is a time to ensure your working environment is a place of safety and connectedness.

Fostering a culture of belonging in your organization is critical with the rise of hybrid work. Working remotely strained the bonds of trust and connection, even for teams who were in good shape before the pandemic. Additionally, new employees who onboarded the past two years have not been able to fully develop those important connections and trust with their teams.

Belonging is a core human need that drives many of our behaviors and desires. It also enhances the meaning of life and fuels many of our deepest emotions. Researcher Dr. C. Nathan DeWall claims, “Humans have a fundamental need to belong. Just as we have needs for food and water, we also have needs for positive and lasting relationships. This need is deeply rooted in our evolutionary history.”

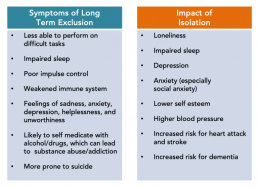

This is why isolation or loneliness is so damaging, causing impaired sleep, depression, anxiety (especially social anxiety), lower self-esteem, higher blood pressure and even elevated levels of cholesterol.

True belonging requires authenticity and vulnerability. But many workers don’t feel that they can be either. One Harvard study found that 61 percent of employees “feel pressure to “cover” some facet of their identity at work.”Hiding or covering was even higher for LGBTQ employees (83 percent), Black/African Americans (79 percent), women (66 percent), Hispanic/Latinx (63 percent), Asian/Pacific Islander (61 percent) and even heterosexual, white men (45 percent) who often felt they had to cover their age, disabilities or mental health.

Here are five science-based strategies to create a culture of belonging.

Make psychological safety a priority

Psychological safety operates as the bridge between surviving and belonging and has proven to be a game-changer in the workplace. Harvard professor Dr. Amy Edmondson defines psychological safety as “a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up.” That bar is low, yet many teams don’t have that because there is a culture of “blame and shame” in place. Edmondson further states that there is a, “shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking,” where trust and mutual respect allow people to be themselves.

It’s important to note that psychological safety is not about being universally liked by others or protected from opinions or beliefs that you find uncomfortable. It’s about openness and confidence that the team won’t penalize someone for speaking up. A healthy team welcomes the input and feedback because it might just be crucial for success.

Google conducted an extensive global study of their teams on what distinguished the best from the average and poor. They replicated Edmondson’s findings, discovering that psychological safety was more important than other factors, including the quality or performance level of the individual members. They found that the best teams did two things: They engaged with each other in a consistent practice of empathy, and they went beyond inviting people to share their thoughts to actively seeking out every member’s contributions.

Edmondson calls this behavior “teaming,” a different way of engaging with each other that enables teams to do their best work. In addition, Edmondson found that the team leader must actively create psychological safety because their position of power naturally suppresses a group’s ability to speak up. Effective leaders intentionally invite opinions, ideas, challenges and critiques. When training your team leaders and managers, they must understand what psychological safety is and how they create it. Psychological safety should be a central element when evaluating the performance of managers and team leaders.

Leverage in-person interactions

While technology makes it possible to work with others through a video screen or phone, our brains were built for in-person interactions. Our brain reads meaning and intent in others through micro-muscular changes in the face as well as body language, and pheromone signals. Much of this information is lost when we are not gathering in person, and even video loses the third dimension that can make the difference in accurately reading another’s emotion. Zoom fatigue is real because our brains have to work harder when missing all that critical data. The same amount of in-person meetings are not nearly as exhausting and can even energize when the group has trust and psychological safety.

When teams are in the early trust-building stage of their time together, it’s best if they meet in person. This not only adds the biological data our brains crave, but it also creates those informal and spontaneous moments where people chat about their lives. So much of the trust-building process lives in those small interactions where we talk about our pets, what we did over the weekend, and other things like favorite foods, interests and families.

When you can’t meet in person, you must intentionally counterbalance this loss with more frequent and in-depth interactions that include team-building outside of conversations about the task or project. While it may seem faster to launch into the project at hand, you’ll lose time later as the team struggles with a lack of alignment, trust and even intense conflict.

As we start to return to the workplace after months of being apart, in-person is especially helpful for bridging the journey back to connection. As a leader, prioritize some in-person team-building events and time for interpersonal interactions. Even masked and outside gatherings will boost the team’s energy and provide biological information that accelerates the bonding process.

Make inclusion your focus

While we hunger for belonging (the feeling of being part of something; mattering to others), it’s important to remember that we get there through inclusion (intentional acts designed to help people feel part of something). To truly understand the power of inclusion, we must look at the terrible harm that exclusion causes. Exclusion is painful, both physiologically and psychologically, and it does lasting damage to your organization.

Researchers from universities such as Harvard, Purdue and UCLA have found that feelings of exclusion light up the same areas of the brain as physical pain. Think about that. Perhaps it’s because emotional injury is just as threatening to our survival as a physical one. Purdue psychologist Dr. Kipling Williams states, “Being excluded is painful because it threatens fundamental human needs, such as belonging and self-esteem. Again and again, research has found that strong, harmful reactions are possible even when ostracized by a stranger for a short amount of time.”

When the part of the brain that processes social status senses that an individual is at risk of being excluded or marginalized by their group, the fight-or-flight response of the amygdala takes over. Not only does this inhibit skills like logical analysis, creativity and innovation, but when it happens across the workforce, it also creates a significant decline in employee engagement, productivity and even physical health.

Neurologically speaking, a sense of security is required to settle the amygdala. As employees gain confidence in their situation and value within a team, they perform better. As they perform better, their confidence increases and a positive feedback loop reinforces these outcomes.

In this sense, it’s not enough for organizations to hope to avoid exclusion. Instead, they must take concrete steps to actively create inclusion and belonging. Managers need to be trained in how to create psychological safety, and leaders need to provide all employees with the knowledge and tools to combat bias and create an inclusive workplace.

Dr. Christine Cox states, “If you are not actively working to make your team members feel part of an inclusive, supportive group, then there are a number of ways (many subtle and unintentional) that you may be creating an environment of social exclusion and its resulting negative consequences.”

Onboard with intention

Our feelings of belonging (or not) within an organization begins with the hiring and onboarding process. And with The Great Resignation driving a war for talent we haven’t seen in two decades, this crucial part of the employee lifecycle deserves your attention.

Employees don’t need to be popular or liked by everyone, however, they do need to feel a sense of belonging with someone. This has lots of implications for workplaces today. Employee engagement is not just a measure of work pride and productivity — it’s also a valuable indicator of inclusion and exclusion. This is why so many engagement surveys include questions such as, “Someone at work cares about me as a person,” or “I have a friend at work.”

Onboarding efforts are more effective when companies go beyond the basics of new employment and help new hires integrate socially into their new community. Did you know that one-third of new hires quit their job within six months of starting it? Currently, we are seeing a sharp rise in ghosting behavior, both by applicants and up to 25 percent of new hires who fail to show up for their first day.

According to one study, 17 percent said that simply a friendly smile or a helpful co-worker would have made all the difference. Nearly 10 percent wished for more attention from their manager and coworkers. Another study found that high-performing organizations are two-and-a-half times more likely than lower-performing ones to assign a mentor or buddy during onboarding. This small and affordable effort helps new hires feel connected, plus their experience is seen by someone who can advise and guide them should they hit challenges.

Encourage mistakes and celebrate failures

A study on team effectiveness, researchers found that the highest-performing teams have an above-average rate of reporting mistakes and errors. When people feel safe enough to mention their errors, they can hold themselves accountable while helping the rest of the group benefit from the learning experience. Teams that acknowledge mistakes early can address and fix them immediately rather than ignore them and letting them fester into bigger problems later.

One study suggests that only 1 percent of employees feel “extremely confident in voicing their concerns in crucial moments.” Amid a global return to the workplace, open communication is especially critical. By framing failures as a powerful source of information and learning insight, leaders can foster an environment of psychological safety by combating “blame and shame” tactics that shut people down (and the organization’s potential along with it). Think of the word “fail” as an acronym for First Attempt In Learning.

The good news is that our brains are wired for connection, helping us create meaningful bonds. But how we build and manage teams can activate those brain structures for either trust and collaboration or conflict and competition.

We are at a time when the world’s workforce is more exhausted and burned out than ever before. The return to in-person work will be stressful, and psychological safety is crucial for it to go as smoothly as possible. Leaders have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to use this time to both revise and reform their workplace culture. The ones who do will reap benefits for decades to come.