Raising The Resilience Of Your Organisation

As an organisation, you need to be ready for the next challenge. To do that, you must view yourself and your business as a whole system, with multiple moving parts that require constant monitoring and adjustment.

We wanted to share this article from McKinsey that discusses this further.

Repeatedly rebounding from disruption is tough, but some companies have a recipe for success: a systems mindset emphasizing agility, psychological safety, adaptable leadership, and cohesive culture.

Resilient organizations don’t just bounce back from misfortune or change; they bounce forward. They absorb the shocks and turn them into opportunities to capture sustainable, inclusive growth. When challenges emerge, leaders and teams in resilient organizations quickly assess the situation, reorient themselves, double down on what’s working, and walk away from what’s not.

Cultivating such organizational resilience is difficult, however—especially these days, when business leaders, frontline workers, and business units are being buffeted by multiple disruptions at once. (Think of the war in Ukraine, the decline in markets, the global pandemic and resulting Great Attrition in talent, and increased evidence of climate change.)

This most recent bout of misfortune and change is vexing in its own way. After all, how often have economic downturns coincided with talent shortages, for instance, or been driven by supply chain challenges? But the reality is, there is no shelf life on change and no expiration date on organizational resilience. There will always be more uncertainty, more change, and a constant push for teams to realize outcomes more quickly. The companies that cultivate organizational resilience—driven not only by crisis but also by opportunity—can gain an important, lasting advantage over competitors.

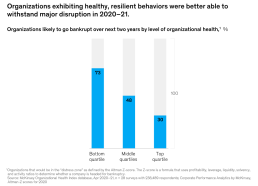

For proof, consider McKinsey’s early research on the relationship between companies’ organizational health and their financial performance during the COVID-19 pandemic: it shows that those businesses exhibiting healthy, resilient behaviours—such as knowledge sharing, performance reviews, and bottom-up innovation—were less likely than “unhealthy” organizations to go bankrupt over the following two years (exhibit).

Where should organizations start? McKinsey’s body of research and work over decades with organizations seeking to be more resilient points to the need to bolster capabilities at four levels.

- They can build an agile organization; a shift toward faster, federated, data-informed decision making and “good enough” outcomes can make it easier for leaders and teams to test, learn, and adjust in the wake of complex business challenges.

- They can build self-sufficient teams that, when held accountable and given ownership of outcomes, feel empowered to carry out strategic plans and stay close to customers, and which, through premortems, postmortems, and other feedback loops and mechanisms, have the information they need to continually change course or innovate.

- They can find and promote adaptable leaders who don’t just react when faced with, say, a natural disaster, a competitor’s moves, or a change in team dynamics. They take the time to coach team members through the change. They catalyze new behaviors, and they develop capabilities that can help set the conditions for both a short-term response and long-term resiliency.

- And they can invest in talent and culture—now and for the future. The companies that focus on building resilient operations, teams, and leaders may gain a two-way talent advantage: such adaptable environments are more likely to attract top talent who will have a greater chance of success and, in turn, be more likely to perpetuate a cycle of resilience.

Senior management will need to tackle all four of these capabilities in the short term—probably simultaneously. They will have to assess the speed at which they make decisions (which, if you ask most managers, is usually not fast enough), whether existing operating models allow for quick pivots when markets change or disruptions occur, and whether their employee value propositions are attracting the “right” talent.1

It will take time to cultivate organizational resilience, but taking steps now can pay off later. Previous McKinsey research shows that, during the last economic downturn, about 10 percent of publicly traded companies in the research base fared materially better than the rest. A closer look at these “resilients” shows that by the time the downturn had reached its trough in 2009, their earnings as measured by earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) had risen 10 percent, while industry peers had lost nearly 15 percent in EBITDA.2

An agile organization is a resilient organization

Many organizations were forced to revamp their strategies, operations, and employee value propositions quickly during the COVID-19 pandemic, given supply shortages, customers’ changing needs, and employees’ changing expectations for what the typical work environment should look like. Some, but not all, have told us they intend to learn from those experiences and continue on an agile track so they’ll be better able to meet future challenges. They recognize that each crisis or opportunity is different in its own way, and so may require different kinds of structures and resources, deployed in different ways, at different times. Beyond just pursuing uptime in operations (physically bolstering production capacity, supply chains, technology systems, and the like), these companies have found ways to build flexible, resilient environments that allow for dynamic, efficient decision making and better time management.

Dynamic decision making. In most companies, specific decision-making authority is rarely spelled out. The question of “who has the D?” can send teams and individuals running in different directions looking for approvals, and, as a result, important business decisions can end up being stalled.3 This can be especially problematic during times of crisis or disruption, when business leaders are aiming for both speed and quality when it comes to decision making, often without understanding that it’s not an either/or proposition. It does no good, for instance, to move fast on a procurement decision only to have to reverse course a month later because one leader failed to get input from other functional leaders on the terms of that decision.

To accelerate their decision making, leaders should pause to distinguish among the types of decisions (big bet, cross-cutting, delegated) they may be required to make, as well as the level of risk involved, and adapt their approaches accordingly.4 Particularly for big-bet decisions, it may be useful for companies to establish a nerve center or a decision-making body comprising a subset of senior leaders or key stakeholders who can respond to events in real time, using real-world data. This team would report back to the CEO and others in senior management frequently to ensure alignment, but it would be empowered to act quickly on daily decisions.

Apart from distinguishing among different types of decisions, business leaders should encourage employees to continually explore for themselves the question of “who has the D?” and, for each specific situation, clarify what needs to be communicated, who needs to be consulted, and, ultimately, who has the final call. To encourage more accountability and transparency, one renewable-energy company established a 30-minute “role card” conversation that managers needed to have with their direct reports. In these conversations, managers explicitly laid out the decision rights and accountability metrics for each direct report. Through this effort, the company sped up the decision-making process and ensured that its decisions were customer focused.5

Effective meetings and time management. A recent McKinsey survey found that, in the post-COVID-19 era, 80 percent of executives were considering or already implementing changes in the content, structure, and cadence of business meetings—this, after taking time to ask themselves, what are these meetings actually for? In one consumer-goods company, for instance, meetings must now be 30 minutes or less and attendees are required to review materials in advance; the time is to be used for true problem solving, not presentations. Other companies have designated certain days as meeting-free or focused on tasks that facilitate innovation, such as peer-learning labs and hack-a-thons. But it may not be enough to look only at meeting hygiene; leaders and teams should also take a moment to ask themselves about their own time-management practices and priorities: Are they in the room with the right people at the right time? Are they spending sufficient time with their direct reports? Leaders and teams should plan to come back to these questions occasionally—at the beginning and end of every new project, for instance, or when changing roles or responsibilities.

Self-sufficient, empowered teams foster resilience

The actual work of the organization should be carried out by teams that, when faced with new and imperfect information, feel motivated and empowered to act. To cultivate organizational resilience and to ensure adaptability, companies will need to think differently about how teams are structured and managed, as well as how they’re connected across the organization. What’s more, companies will need to provide support systems that allow employees to engage in creative collisions and debates, give and share feedback honestly, and continually incorporate that feedback into their routines so they will be better able to adapt to any future challenges.

To cultivate organizational resilience and to ensure adaptability, companies will need to think differently about how teams are structured and managed.

Team management. Rather than continually tell teams what to do, leaders in resilient organizations minimize bureaucracies and foster entrepreneurship among and within teams. They nearly always put decision making in the hands of small cross-functional teams, as far from the center and as close to the customer as possible. They clarify the team’s and the organization’s purpose, provide some guardrails, and ensure accountability and alignment—but then they step back and let employees take the lead. The Disney theme parks provide a good example: every employee is dubbed a cast member, and their clear objective is to create “amazing guest experiences” within a set of guardrails that includes, among other responsibilities, ensuring visitor safety and fostering family-friendly behaviors. Meanwhile, a large multinational manufacturer has divided itself into thousands of microenterprises with about a dozen employees in each. The microenterprises are free to form and evolve, but they all share the same approach to target setting, internal contracting, and cross-unit coordination. The shift has created an innovation mindset among employees.

Another characteristic of resilient organizations is their ability to break down silos and use “tiger teams” to tackle big business problems. These are groups of experts from various parts of an organization who come together temporarily to focus on a specific issue and then, once the issue is addressed, go back to their respective domains. For instance, when a financial institution needed to divest several major assets, it convened a small project team made up of members of the finance team and the business units to identify and execute on all of the steps required over the next nine to 12 months to eliminate stranded costs from the deal. This freed up leaders in the financial institution to focus on other important elements of the divestiture.

Support systems. Employees are unlikely to change their behaviors if failure is not an option—instead, they will respond to crises or transformational opportunities by hiding problems that will inevitably arise when trying new things, averting the risks that come with innovation and change, and being afraid to ask questions. Organizations that have cultivated a resilience response emphasize psychological safety (or the idea that taking some personal risks can be OK) and continuous learning. Business leaders in these companies continually ask teams—and themselves—whether they feel as though they have the space to bring up concerns or dissent, whether they fear retribution for mistakes, whether they trust others, and whether they feel valued for their unique skills and talents. Based on the answers to these questions, business leaders can take steps to better support their employees.

They may create new ways of recognizing individual and team performance—through monthly innovation awards or other prizes that acknowledge employees’ attempts as much as they do employees’ outcomes. They may build pre- and postmortems into all projects, for example, so team members have a voice or an opportunity to raise concerns and learn from both successes and mistakes in an open environment. At one financial institution, the owner of a business meeting typically designates one person in the room as an impartial observer whose job it is to provide feedback after the session about what worked and what didn’t.6

Adaptable leaders set the conditions for resilience

Adaptable leaders enable organizational agility and team empowerment and ultimately set the tone for resilience—which is why it’s so important for companies to identify the traits that set these leaders apart, build them into the company’s performance evaluation processes, and promote the work that these leaders do. So what does it mean to be an adaptable leader? It means not only reacting to a crisis or pressure situation but also finding the lessons in the situation and continually coaching and encouraging individuals and groups to do the same. It means acknowledging that you (like everyone else) may not have all the answers and being willing to ask a lot of questions.

In our experience, adaptable leaders are more likely to embrace workplace paradoxes rather than viewing everything as either right or wrong. Another cut of McKinsey’s early research on the relationship between companies’ organizational health and their financial performance during the COVID-19 pandemic shows that the trait of “challenging leadership”—or the idea that adaptable leaders call upon employees and teams to step out of their comfort zones and think and work differently to achieve a goal—was one of the organizational health practices most correlated with resilience.

Adaptable leaders tend to have a systems mindset, looking for patterns and connections, and so are more likely to see opportunities where others see problems. They can set a direction without being entirely clear about the destination. They take time to define a cultural DNA—or behavioral code that guides how decisions are made, priorities are set, and work gets done. They embark on frequent listening tours—in-person and through virtual town halls, for instance—to understand what employees need at different stages of their careers in the organization.

They take advantage of pulse surveys and other mechanisms for getting real-time feedback on changes to operations, staffing, external communications, or other business activities. They introduce new practices that are not only effective during crises but that can be adapted to address everyday business challenges, and they set a strategic direction that is grounded in purpose and outcomes rather than in just checking boxes—so when the organization needs to shift to a new business model or otherwise make trade-offs after a crisis, the change may engender more buy-in and speed in execution.

That’s what Northrop Grumman did in early 2020, according to CEO Kathy Warden. The company rearticulated the behaviors that had formed a set of guiding values for the company. “We paired those values with leadership behaviors, and we provided our leaders with tools and training so they can implement and communicate those values and behaviors with their teams,” she said. “This effort has really given our people a North Star and empowered them to operate within our value system. And over time, it has helped us move faster as an organization.”7

Finally, they preserve employees’ (and their own) energy by emphasizing well-being versus pushing for 24/7 performance and by serving as role models for employees under pressure. Some of the adaptable leaders we spoke with say they take brief reflection breaks (five- or ten-minute pauses) during their busy days, organize walking meetings, and otherwise make time for human connection, renewal, and basic self-care. Research shows that such role modeling can have a positive effect across the organization. A McKinsey survey on employee experience found that taking care of one’s physical and mental health was associated with a 21 percent improvement in work effectiveness, a 46 percent improvement in employee engagement, and a 45 percent improvement in well-being.8

Talent and culture underpin everything—now and for the future

To cultivate a resilience response for the long term, organizations should rethink their approach to talent management and pay attention to critical cultural factors. It’s well-proved that companies that can match talent to strategy are more likely to outperform peers. But McKinsey research shows that about 45 percent of organizations are anticipating skill gaps within the next five years, and about the same number are reporting skill gaps today.9 What’s more, organizations are still reeling from the effects of the Great Attrition: Record numbers of people left the workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic, and those who are returning are demanding greater compensation, flexibility, development opportunities, and purpose at work.10

About 45 percent of organizations are anticipating skill gaps within the next five years, and about the same number are reporting skill gaps today.

Resilient organizations have started to build the structures and capabilities to address current talent-management challenges—and those to come. They have, for instance, invested in analytics to hire, develop, and retain talent more effectively. They are changing their hiring processes to look beyond traditional talent sources, build more diverse slates of candidates, simplify application processes, and speed up decision making. Some are even extending the onboarding experience to cover the weeks just before candidates formally start (to ensure they aren’t tempted by other offers at the last minute). And they are proactively trying to identify and leverage the skills of high-potential employees within the organization, focusing on experience more so than on academic degrees.11 In some cases, executives are realizing, a certificate of specialization or an apprenticeship can suffice as requirements for certain roles.

This may be especially true in the case of technology talent. At a time when every company is a technology company, almost 90 percent of global senior executives say their companies are unprepared to address the gap in digital skills. And while it may feel risky to source and hire candidates with unconventional backgrounds to fill technology roles, recent McKinsey research points to how work experience enhances the value of human capital over time and shows that people coming from different parts of an organization, or even from different fields, are capable of mastering new skills. In this case, hiring for potential rather than the perfect fit can boost internal mobility, employee loyalty, and corporate capabilities long term.12

Organizations seeking to cultivate more resilience will need to be crystal clear about how to adapt their cultures and employee experiences to offer value to a newly empowered workforce and win a changed war for talent, while also ensuring the organization can deliver on its strategy and mission. For instance, some are reassessing their compensation and benefits packages and incorporating the options that employees say they want—for instance, more coverage for mental-health needs or childcare or personal-assistance services, or different forms of flex time.

Others are making concerted efforts to rebuild social capital, much of which has gone dry during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. They are, for instance, introducing social capital as a factor in employees’ career development—through KPIs that target relational metrics (tied to collaboration, apprenticing, and making connections) rather than operational ones. They are investing in programs that encourage greater participation in internal and external networks. Some are even redesigning office spaces to enable more spontaneous collisions among employees.13

The pandemic, geopolitical strife, climate change, and “garden variety” disruptive trends such as digitization and globalization have caused many organizations to stumble in recent years. Supply chain shocks have cost US companies trillions of dollars. Companies are losing talent at unprecedented rates.

But this is where resilient companies hold a clear advantage over others. At a micro level, they demonstrate better shareholder returns and are better than their peers at integrating new technologies, supporting customers, building partnerships, and attracting and retaining employees. At a macro level, they fuel investment in new business, strengthen GDP, enhance productivity, and enable the rapid movement and growth of talent and skills. These companies prioritize leadership development and thus are driven by adaptable leaders who can facilitate the kinds of behavioral adjustments and mindset shifts required to be resilient in the face of change.

Rather than viewing sudden business disruptions as glass-half-empty situations, business leaders would do well to emulate the moves of those in resilient organizations and look at the disruptions as opportunities to make lasting, substantive, positive changes to business as usual—and fill the glass to the top.

Dana Maor, Michael Park & Brooke Weddle – October 12th 2022